As dancers, or aspiring dancers, a lot of us have experienced that tug between the desire of becoming a professional dancer and perhaps the more secure world of a 9 to 5 career position. And, some of us are lucky enough to combine both. Nadine Kaslow has done just that – combined both worlds. Here are excerpts from an article about Dr. Kaslow, (written by Elizabeth Landau, of CNN): “Psychology plus ballet: Meet ‘Dr. Dancer”.

Nadine Kaslow sits with one slender ivory leg dangling, the other tucked neatly under her dress with the heel of her beige pump facing up. These legs have supported her throughout her career as a dancer. But in her head, Kaslow struggled for years over whether to follow that path or her passion for psychology.

She eventually found a way to combine the two worlds, serving not only as a psychologist for the Atlanta Ballet, but also becoming a powerful force for providing accessible mental health care for disadvantaged women.

“I always wore a ballerina around my neck,” she said of the gold charm she’s had since age 13, which she wore Wednesday in her office at Emory University School of Medicine. “But I never talked about going to ballet. I just didn’t think I’d be taken seriously.”

Now, as the new president-elect of the American Psychological Association, Kaslow doesn’t worry about that anymore. Besides being an Emory professor and chief psychologist of Grady Health System, she is also the psychologist for the Atlanta Ballet, where some students call her “Doctor Dancer.”

Kaslow, 56, grew up in the Philadelphia area and started dancing when she was 3. She took classes in creative movement, which involved developing skills such as “prancing like a pony.”

Little Nadine knew she wanted to do something more than what the system had set out for her. She asked her mother who was the head of the school, so she could ask to learn real dance with the big kids. The boss told her she needed to be 5, but this didn’t deter her.

“I’d stand outside the class with the big kids and I would do it in the hallway,” she said. Finally, when she was 4, because of her persistence, she was allowed to start real ballet classes with 5-year-olds.

Choosing psychology

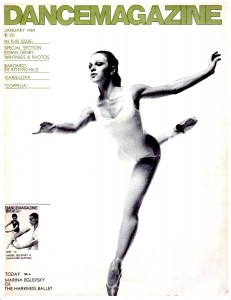

In high school and early college, Kaslow danced with the Pennsylvania Ballet. But when she applied to college, she wrote that she wanted to be a psychologist. It’s what her mother did, too, and she enjoyed reading books about psychological problems.

“I was one of those kids that, when other kids had problems, I was the one they’d come and talk to about their problems,” she said. “I really wanted to help people but I really wanted to understand through the human mind, human behavior and human relationships.”

During graduate school, she continued taking ballet classes. In her head, it was a tug of war over whether she truly wanted a career in psychology or in dance. The director of the Houston Ballet then offered her a choice: She could have a position in the company, if she lost 15 pounds.

Perhaps because of the body-consciousness of ballet, Kaslow remembers with ease how much she weighed at various points in her life. As a Ph.D. student, she said, she was already 12 pounds thinner than she is right now. On her frame, not quite 5 feet tall, an additional 15-pound loss would be dramatic.

“I knew at that point that that was not a healthy lifestyle choice,” she said. “I was old enough and I was out of the system enough that I was able to stop and say that was it. That was my defining moment.”

She got her doctoral degree in 1983 and headed to the University of Wisconsin for her internship and postdoctoral fellowship training

At the ballet

About five years ago, Kaslow started ballet classes at Atlanta Ballet Centre for Dance Education. She met the center’s director, Sharon Story, and the Atlanta Ballet’s artistic director John McFall. It turned out, there was a way to reconcile her passion for ballet with her career in psychology.

Kaslow became the Atlanta Ballet’s first resident psychologist, helping the students and professional dancers through wellness programming and psychotherapy.

“She keeps dancing and brings her knowledge and compassion to our dancers and students to pursue their lives and passions with strength, confidence, and healthy well beings,” Story said in an e-mail. “Nadine is tiny in stature and a huge brilliant gem to all of us at Atlanta Ballet.”

When Kaslow started working with dancers in her capacity as a psychologist, she thought eating disorders would be a huge problem. Instead, she’s found other issues are more prevalent: Performance anxiety, balance between different activities and perfectionism.

Perfectionism in particular is a problem that Kaslow has struggled with herself, and something that she shares with some of the dancers she’s seen in therapy.

“I really talk to the dancers about, how do you think about doing your best, and being good enough, and what a realistic and attainable goal is, and I try to do that for myself as well,” she said.

The cultural norms of ballet are such that it’s hard to know when a dancer truly has an eating disorder, she said.

“When I weighed about 22 pounds less than I do now, I was told I looked like a hippopotamus,” she said. “The problem was that part of me believed them. But I look at myself now and I say, ‘Well, I don’t really look like a hippopotamus now, so I probably didn’t look like a hippopotamus 20 pounds less than this.’”

Kaslow sees many connections between the study of the mind and of human relationships.

“As a scientifically-minded psychologist, I build upon many of the qualities that served me and others well in the dance world — curiosity, persistence, patience, and a passion for the work,” she said. “As an educator, I know that when I am teaching dance or psychology, it is essential that I provide a facilitating environment that nurtures creativity, self-expression, self-acceptance, and a dedication to doing one’s best.”

Her advice to graduates, she said, would be: “Follow your passions and your dreams. I wish I had gotten that message sooner, and that I didn’t feel like I had to choose (between dance and psychology) for so long.”

As the old year passes, I thought a look back at some of this year’s highlights with some of the major ballet companies (and not so major) would be a fitting way to look at where we’ve been and look forward to where we’re going. Below are 10 of my picks for a brief look at the world in ballet for 2016.

As the old year passes, I thought a look back at some of this year’s highlights with some of the major ballet companies (and not so major) would be a fitting way to look at where we’ve been and look forward to where we’re going. Below are 10 of my picks for a brief look at the world in ballet for 2016.