I’d waited months to see this celebrated event at the de Young Museum, and so one day shortly before it closed, I trekked over to San Francisco to view the Nureyev Exhibit. A sense of awe filled me as I walked toward the somewhat narrow opening to the exhibit, and then realized it had been designed to make one feel as if you were part of the production on stage or backstage waiting in the wings.

The entrance was marked by 4 spotlights pointing the way to the exhibit opening. Once through, I entered an almost magical world filled with some of his most opulent costumes (and those of his partners and fellow cast) marking his major ballets displayed in windows behind scrim. Along with videos set up and running of La Bayedère, Don Quixote and one in particular that caught my eye was a large screen with a continuous clip from Pierre Jordan’s 1972 film “Un danseur” (I Am a Dancer) of Nureyev in practice executing series after series of astounding jumps. Well worth the visit – one of the highlights (for me) was seeing how small Margot Fonteyn’s toe shoes really were!

Here are clips from what others had to say about the exhibit:

From musicandmirror.com: “Lots of beautiful costumes, photographs, and filmed ballet clips spanning Nureyev’s career await. Most of the exhibit is laid out in groups of costumes from various ballets, each backed by a small scrim that makes you feel like you’re walking backstage and onstage, as if wandering through several set pieces…”

And, San Francisco Classical Voice (by Janice Berman): “Rudolf Nureyev’s career was as extraordinary as the fact that many people no longer know about it. That will likely be remedied with the de Young Museum’s new exhibit, “Rudolf Nureyev: A Life in Dance,” which opened on Saturday, displaying 80 costumes from France, primarily doublets and tutus by famous designers, that he and his partners wore, along with performance photos.

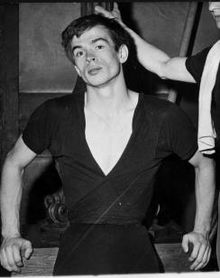

Nureyev, who leapt into view in 1961, was the first dance superstar. His fan base created the phenomenon known as Rudimania. And he had a will, or some might say a whim, of iron.

He was a dancer both gifted and driven. He danced stunningly, then competently, and finally relentlessly, well beyond the moment when he should have stopped. He professed indifference to the critics who said the world’s greatest dancer was in the process of taking it all back. “I don’t want anybody, anytime, to tell me I should go away,” he told me once. “It’s not their life. I don’t tell them to go back to Harvard to study English.”

He was a famously mercurial dance director with a detailed knowledge of the great classical ballets from Imperial Russia. He brought them to the Paris Opera Ballet, where he was artistic director from 1983 to 1989, beginning with La bayadère, which, like other works he staged, was reproduced in other classical companies around the world. He revitalized the career of Royal Ballet prima ballerina assoluta Margot Fonteyn, twice his age, whose stardom, in exchange, helped bring him international prominence. They shared an artistic and personal (how personal, nobody seems to know) partnership that lasted 17 years.

So this exhibit, like Nureyev, transcends the narrative of a life cut short. His tombstone, at Saint-Genevieve-des-Bois cemetery near Paris, was created by Ezio Frigerio, who designed Nureyev’s final production of La bayadère for the Paris Opera Ballet. It’s a mosaic rendition of an oriental carpet, its folds draped over a traveler’s trunk.”

Finally, highlights from review in the Los Angeles Times (by Liesl Bradner): “The exhibition features photographs, videos and other ephemera, but the stars of the show are 70 exquisite costumes from the ballets Nureyev danced in and choreographed, including “Swan Lake,” “The Nutcracker” and “Romeo and Juliet.” The opulent wardrobe pieces, valued from $45,000 to $95,000, are a testament to his obsession with detail.

He was incredibly particular when it came to his costumes. He knew exactly which fabrics to use,” said curator Jill D’Alessandro. “He believed the costume needed to finish the movement, so when the dancer stops, the costume should continue to move and float, like in Ginger Rogers’ feather number in his favorite scene from ‘Top Hat.’”

Rudolf Nureyev was often quoted as saying “you live as long as you dance”…this exquisite exhibit shows us the passion by which he lived.